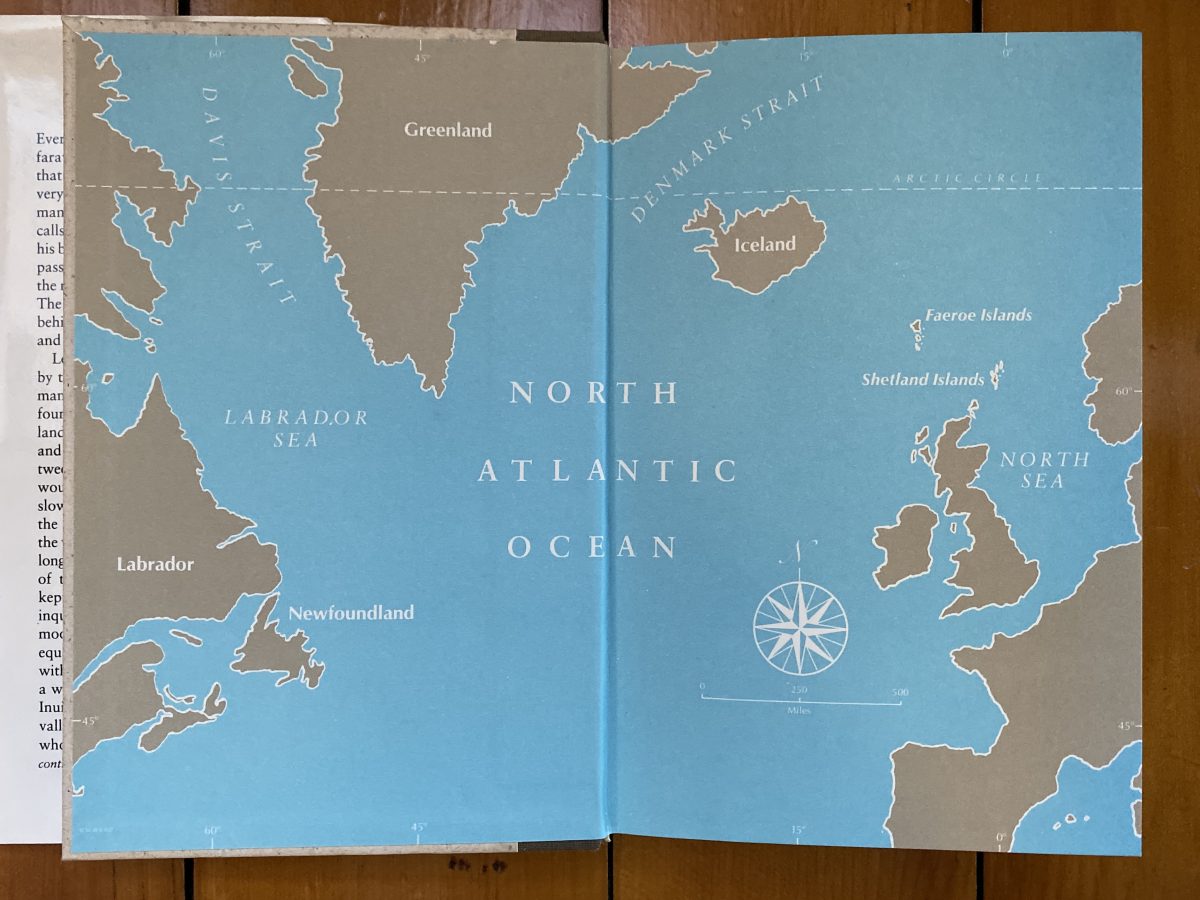

The concept behind Lawrence Millman’s book Last Places: A Journey to the North is such a perfect fit to my interests, and this blog, that I knew I had to read it. Millman endeavors to follow the trail of the Vikings, traveling from Norway to Newfoundland via Shetland, the Faroe Islands, Iceland, and Greenland, mostly via sea and foot, camping along the way. It’s a personal travelog, from an opinionated and seasoned traveler with lots of stories to tell. It’s not his first time in any of these locations, which is perhaps what frees him up to seek the most remote, difficult, or forgotten corners of these already far flung islands.

It was a joy to read Last Places with the book in one hand and Google Maps in the other. Many of the places he visits I knew little about, like Foula, the most westerly and remote of the Shetland Islands. Millman brings Foula to life as he arrives via mailboat, setting up camp while getting dive-bombed by noisy skuas. In what will become a pattern, Foula is the most challenging place he can visit, and he’s there to fulfill a Viking-related goal: find a local who still speaks the Norn, an extinct variation of Old Norse. After wandering the island, meeting peat harvesting locals who look askance at visitors, he finds an old man who teaches him some Norn, including eight different words for varying types of wind.

From Shetland he sails on the ship Norröna to the Faroe Islands (which he spells “Faeroe Islands”). The book was published in 1990, so one assumes his travels were at least a few years earlier. Over 30 years later, the Norröna still sails between Denmark, the Faroes, and Iceland — but not Shetland. There are however rumors of a Norröna Shetland stop coming back.

In the Faroe Islands chapter, it was fun to spot differences between today and the late 1980’s. Most noticeable was the lack of tunnels, both the subsea variety connecting Vágar to Streymoy and those that burrow through mountains to make tiny, isolated villages less remote. His first stop was Gásadalur, home of the famous Mulafossur waterfall, but unlike today he has to hike the old alpine route over the mountain of Knúkarnir to get there. His diary entires include scenes of camping in the treeless mountains, a boat trip to Mykines, and by chance the experience of witnessing a grindadráp (whale hunt) first hand, complete with celebratory chain dancing that evening. His relatively short visit to the Faroes ends with someone informing him that the Løgting (parliament) has allotted money for a tunnel to Gásadalur, which he regards as “gloomy news” given his love of isolated outposts. He shouldn’t have worried though, since it would take more than 15 years for that tunnel to be completed, in 2003.

The bulk of Millman’s trip, or at least of the book, is spent in Iceland and Greenland. Along with his current travels, he includes stories of past trips, and meets up with friends from those previous journeys. In Iceland, following the theme, his itinerary is full of difficult to access locations. He travels through volcanic highlands to Lake Askja, catches a ferry to Grímsey Island (40km off the northern coast), and visits a lighthouse keeper in Hornbjarg on the northern tip of the western fjords. Although I’ve been to Iceland twice, those trips combined were less than 10 days and the vivid scenes in Last Places only amplify my desire to go deeper off the ring road, far from where an economy rental sedan can take me.

The remote lighthouse was perhaps the most enchanting of the Icelandic scenes, perched on a cliff high above the ocean and maintained by a keeper named Jóhann.

“Don’t you feel lonely here?” I asked him, noting that he was the only year-round resident for seventy miles with fewer than four legs or less than two wings.

“Look at those lovely cliffs, my friend! Look at that mist on the ground! Listen to the rush of that stream! How can a man be lonely with such companions?

Last Places (Chapter 8: The Lighthouse at the End of the World, page 133)

Of all the scenes in which I wished for a photograph it was the lighthouse where the omission felt like a loss. A mountain or a lake has a timeless quality, perhaps similar to what I might experience today, but the lighthouse was a character of its time. If such a photograph existed it would surely be featured on innumerable Pinterest boards, as apparently the walls were completely lined with over 16,000 books. As an introvert, a bibliophile, and a fan of small places, I certainly wouldn’t mind spending a month or more shacked up in such a literary lighthouse. Jóhann, the lighthouse keeper, seemed to agree, as the chapter ends with him lamenting his mandatory retirement at age 70. I doubt the books are still there, but today it appears that the dream of staying in the Hornbjarg lighthouse could come true, for the astronomical rate of $1,330 USD a night.

From Iceland to Greenland, this time by air since Millman failed to find a ship heading westward. His account of the Greenlandic people was strangely critical, often painting the locals in an uncharitable light and describing Nuuk as rundown and littered with Carlsberg bottles. Having never been to Greenland, it was harder for me to imagine or keep track of his travels via ship and plane. His journey starts in the south, landing in Narsarssuaq and trekking overland from Igaliku to Qaqortoq. He then criss-crosses the island, from Nuuk on the west coast to Kulusuk on the eastern side. If nothing else, these chapters helped me map the inhabited outposts on the edge of this massive ice sheet, the start of a deeper Greenlandic rabbit hole I look forward to going down.

The final destination in this Viking journey is Newfoundland and Labrador, of particular fascination for me, having just visited last summer. Although my wife and I managed to travel the length of Newfoundland during our 10 days there, we didn’t see any of the places that Millman reveals to his readers. He begins in Goose Bay, Labrador where he hires a local guide to escort him to Eskimo Island. We learn about political history in passing, as locals discuss the effects of Joey Smallwood’s Fisheries Household Resettlement Program. At the end of the book he finds his last location in Newfoundland, traveling south to the northernmost point of most tourist maps. It’s a fitting end to his journey: the UNESCO world heritage site of L’Anse aux Meadows, the remains of an 11th-century viking settlement and the oldest presence of Europeans in North America.

Last Places reveals idiosyncratic details about the places that Millman travels, colored by his own history, politics, and viewpoints. It’s a 4-month travel diary, an ode to inhospitable landscapes, and an attempt to both spotlight and hold on to the uniqueness created by isolation. It’s value for me, beyond the enjoyment of tagging along on such an epic trip, was the new pathways it opened for continued exploration. Every couple of pages I had something new to map and bookmark, parts of Millman’s viking journey that I can now blend in with my own.