I could fly to the Faroe Islands right now. It would take a few connections from Pittsburgh, but soon I’d be looking out the window of an Atlantic Airways flight and trying to name the islands, if I could make them out through the fog. But that accessibility is a modern phenomena, and for most of its history the tiny archipelago was a distant place, a significant sea journey from anywhere. Isolation required self sufficiency, which led to a unique food culture, distinct even from its Scandinavian neighbors. Fermented lamb, boiled pilot whale, braised guillemot, puffin stuffed with cake. These dishes bear the imprint of the landscape itself. Faroese food is the creative output of natural constraints, defined by both what was missing (fertile soil, salt) and what was plentiful (steep bird cliffs, grassy mountains, deep ocean inlets).

Koks Restaurant

During the week that my wife and I spent in the Faroe Islands, in July of 2018, we prepared most of our own meals. We moved around a lot, from Tórshavn to Hvannasund to Víkarbyrgi, and developed a routine of stocking up at the closest Bonus and cooking in our Airbnb. I knew about traditional Faroese food, from the excellent article by Rebecca Mead in The New Yorker, published just a month before our trip. She profiles Koks, a Michelin star restaurant in the Faroes that focus on local and traditional cuisine. I found her description of the food at Koks fascinating, but not necessarily mouth-watering. I couldn’t have gotten a reservation that quickly anyway, but I also wasn’t sure I was up for it. As she notes, “Koks gleefully embraces the potentially disgusting aspects of Faroese cuisine.”

A generation ago there were hardly any restaurants in the Faroe Islands, and even today there are few options outside of the largest cities of Tórshavn and Klaksvík. Head chef at Koks, Poul Andrias Ziska, told Mead that traditionally, “paying for food is considered crazy. You have the fish in the ocean, and you have a boat, or you know someone who has a boat, and you go out and get it and cook it yourself — that’s the mentality.” So even when restaurants starting opening, they tended to focus on food from elsewhere. Koks was an anomaly in this environment, catering to high-end diners, and serving traditional dishes via small plates over a dozen courses. The restaurant is a symbol of the county’s accessibility to a global audience, with foreign foodies traveling thousands of miles for the ultimate local meal.

Perhaps because of this appeal to foreigners, Koks opened first inside hotel Føroyar, in the capital city of Tórshavn. It later moved to the village of Kirkjubøur, 15 minutes away on the western coast of Streymoy. Today the location is more extreme, housed in a turf-roofed farmhouse from 1741, nestled in a valley near Lake Leynar. Koks sits alone in the mountain valley, surrounded by the nature its ingredients are drawn from, isolated from other homes, businesses, or even a proper road. Diners meet at a designated spot and climb into a 1991 Landrover Defender for the last leg of the trip, which includes fording a stream.

Fermented Lamb

One of the most unique dishes in the Faroe Islands, certain to be on the menu at Koks, is skerpikjøt, or wind-dried mutton. If you’ve been to the country, it’s not a surprise that sheep play a vital role in the cuisine, since even today they outnumber humans. But preserving the meat of these plentiful animals hasn’t always been straightforward. In The Nordic Cook Book, Magnus Nilsson describes how until recently (the last few hundred years) salt wasn’t available in the Faroes, and even then it was too expensive for most people:

“The Faroese climate is too cool to evaporate seawater in salterns and there are no naturally growing trees on the islands to fuel saltpans. This situation, combined with the Islands’ remoteness, especially during the era of sailing ships, has historically made salt a rare and expansive community.”

The Nordic Cook Book by Magnus Nilsson

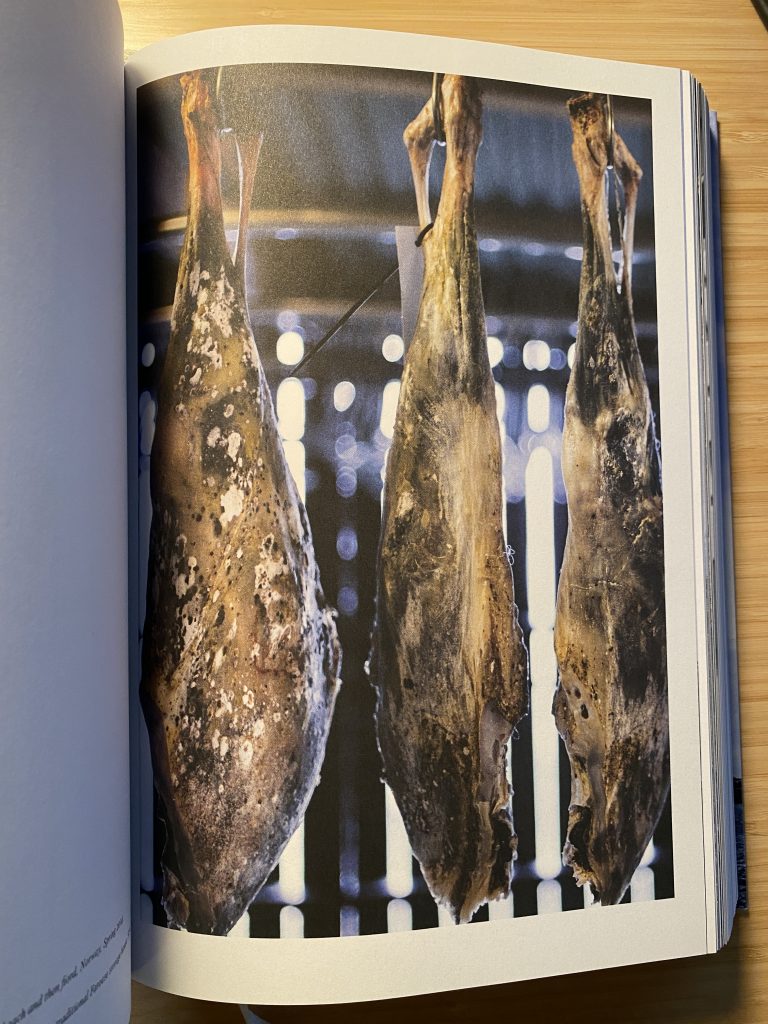

So instead of salt curing the sheep, the Faroese developed a technique where slaughtered lambs are hung in a hjallur, a drying shed with walls made of tightly spaced skinny boards that allows for the wind to blow through. The technique is quite slow, taking up to a year to reach full maturation.

“Joints of freshly butchered lamb are hung in a wooden shed, known as a hjallur, that is chinked with drafty gaps, allowing the islands’ incessant winds to blow through it. Wind and time bestow on the meat a layer of greenish mold, and a pungency somewhere between Parmesan cheese and death.”

Profile of Koks in the New Yorker by Rebecca Mead

In his book, Nilsson describes three stages of skerpikjøt development. The first is known as visnað (withered) and must still be cooked if eaten. The next stage is ræst (semi-dry) and is described as the most difficult for an unaccustomed person to stomach, as it’s “pretty much decaying meat.” It‘s coated in a crust of mold that has to be scrapped off before thinly slicing the meat, which is often eaten raw with bread. The final stage is called turrur (dry) which is actually milder in flavor and similar to a saltless charcuterie.

“The Faroese language has dozens of words for degrees of rottenness: stadnaður means ‘dried on the outside, soft on the inside’; karmoðin means ‘completely rotten’.”

Profile of Koks in the New Yorker by Rebecca Mead

Traditional Producers

Stóra Dímun is one of the most remote places in the Faroe Islands. Just two (related) families live there, with ancestry on the island that dates back over 200 years. While researching for the Nordic Cookbook, Chef Magnus Nilsson worked with Jógvan Jón and Eva of Stóra Dímun on many of the Faroese recipes, which you can read about in the article he published in Roads and Kingdoms.

The couple maintain a largely self-sustaining lifestyle, raising sheep and cattle, growing turnips and kohlrabi. There’s a large hjallur on the island, supporting the fermentation process for their own consumption as well as sales on the mainland. In 2017 the family won the Embla Nordic award for best food producer, where it was noted that all their food is “produced using traditional techniques in innovative ways and with respect for the environment.” This year they’ve launched a new product, a turnip brew made in collaboration with the Okkara brewery.

Home Hospitality

When I return to the Faroe Islands, I might try to get a reservation at Koks, or maybe Ræst, another restaurant that focuses on traditional foods. But I will definitely try heimablídni, an experience where you dine in regular people’s homes. These underground restaurants are available on most of the islands, often in villages where there is no restaurant option. The concept actually grew of the need to provide tourism services in remote areas, and has been formalized by the government using similar regulations as the direct sale of farm produce. I love the idea of making a deeper cultural connection while also getting a chance to try these traditional foods. Even if my palette might find some of the flavors unpleasant, I’m too curious not to try for myself.