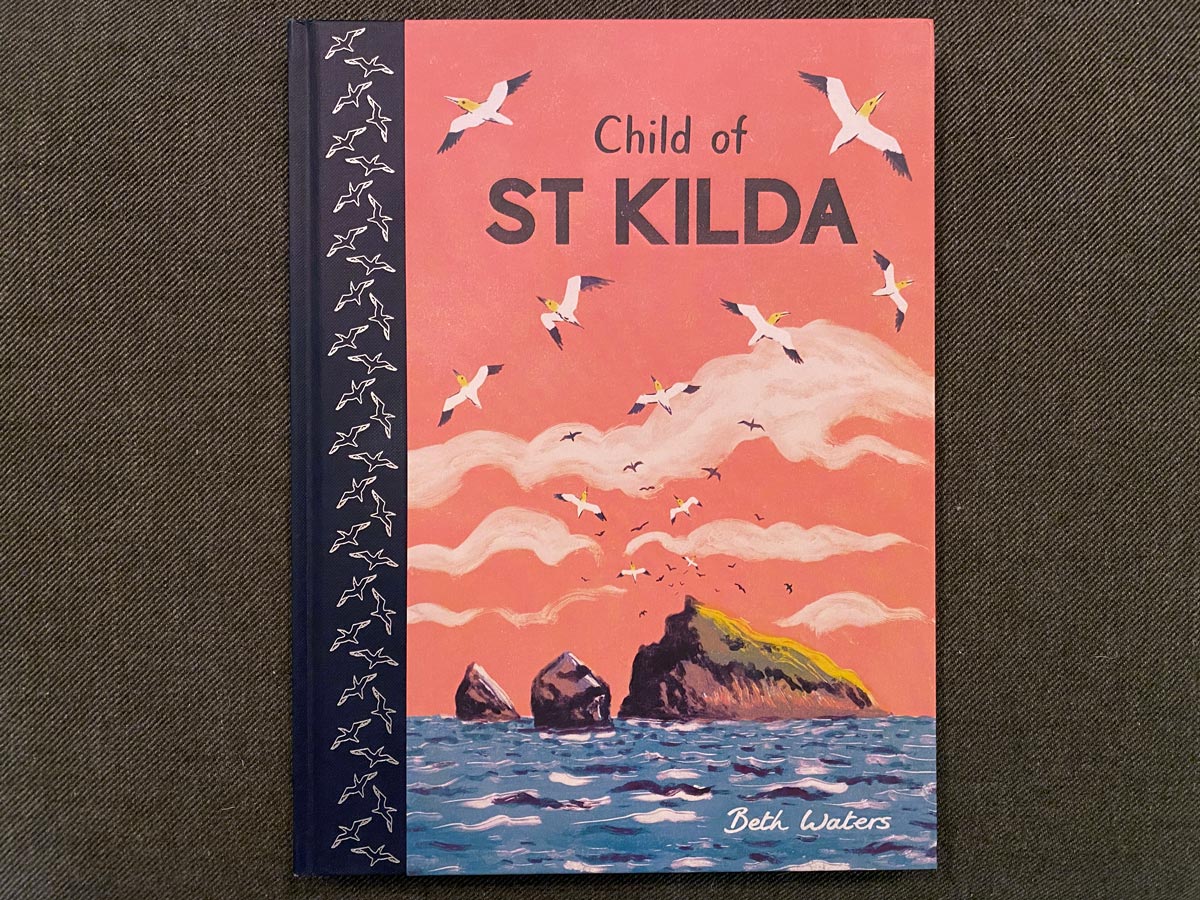

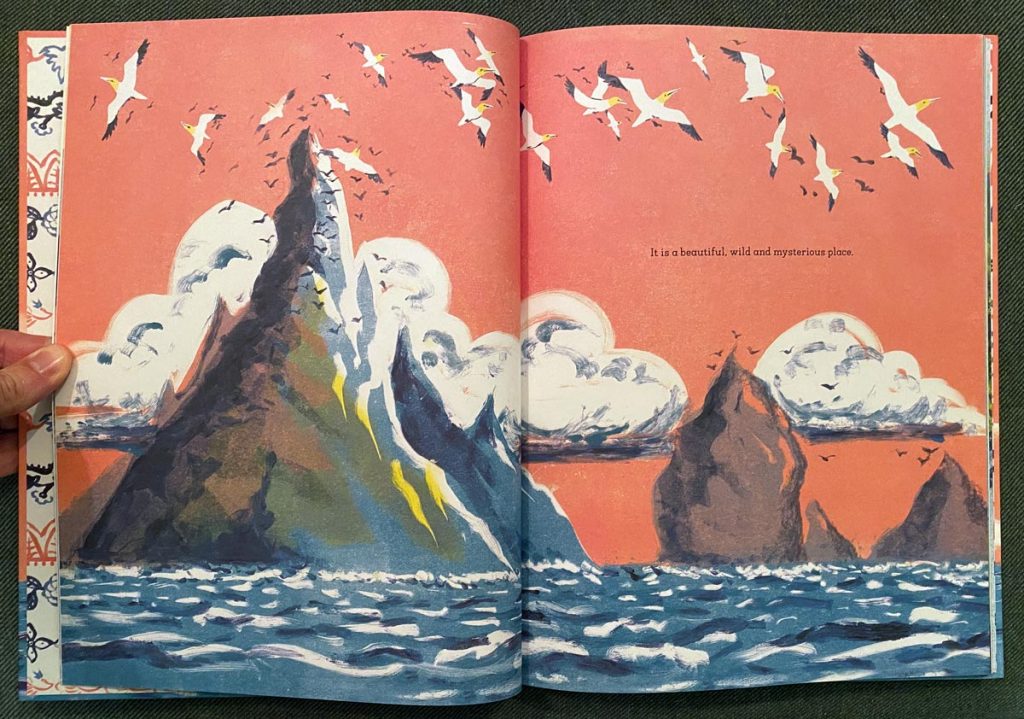

Off the west coast of Scotland lay the Outer Hebrides, a chain of islands that look almost like a shield being held up by the mainland to protect itself from the rugged North Atlantic. Beyond that, a full 40 miles further west, are the lonely islands of St. Kilda, a tiny archipelago forged by volcanos and sculpted by violent winds and waves. It’s not exactly a convenient place to live, and yet these islands were occupied for nearly four thousand years, an incredible testament to subsistence living and human perseverance. The story of life there, and the eventual decision to evacuate, is the unlikely subject of an illustrated children’s book called Child of St. Kilda by the British author, illustrator, and printmaker Beth Waters.

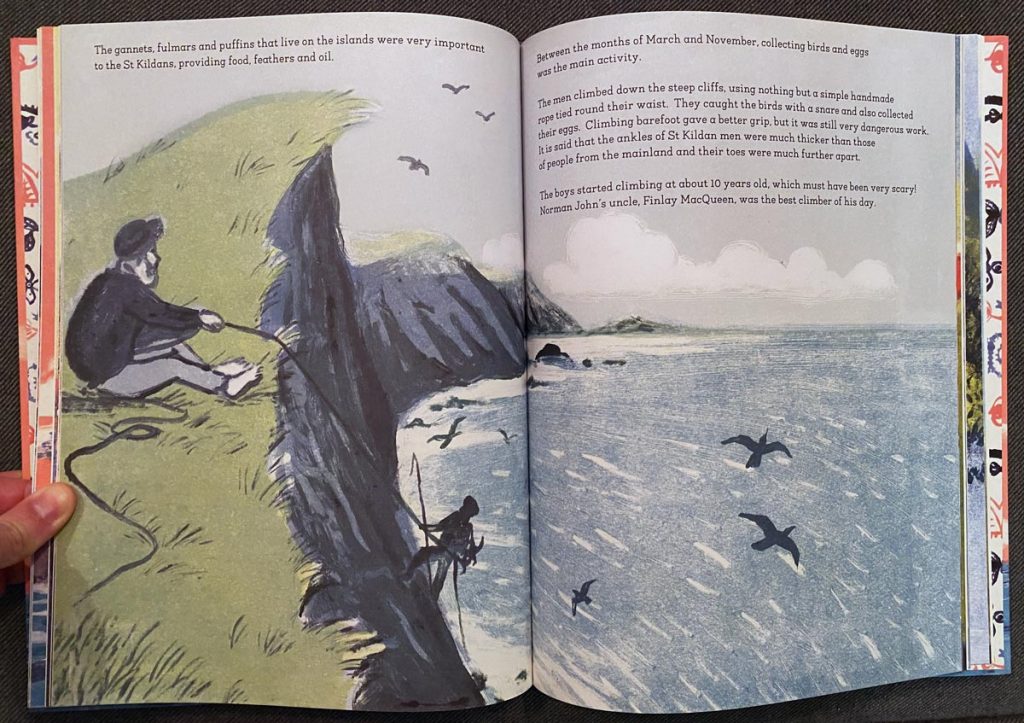

At its peak, the islands were home to 180 people, but numbers dwindled throughout the 1800s due to sickness and emigration. In 1930, just as steamships made travel to the island more feasible, the final 36 villagers decided to evacuate and St. Kilda was abandoned. The story in Child of St. Kilda begins just a few years earlier, following the life of a boy named Norman John Gillies who was born in 1925 on Hirta, the largest of the islands. Waters’ illustrations paint a well rounded vision of childhood on St. Kilda as we learn about families, village rituals, the seabird hunt, and the small school and church. It’s the life of a boy who has never known another place, for whom these islands are the entire world.

The isolation of St. Kilda meant that people survived on whatever the land, sea, and air could provide. A large portion of their diet was made up of puffins and gannets, the dramatic cliffs of the islands home to nearly a million seabirds during breeding season. They also raised sheep, including a unique breed that are genetic remnants of the Neolithic Era, native only to their namesake island of Soay. The remoteness also meant that the closed community had limited defenses against outside disease, and the population was nearly decimated after visitors in 1727 brought smallpox and cholera to the islands.

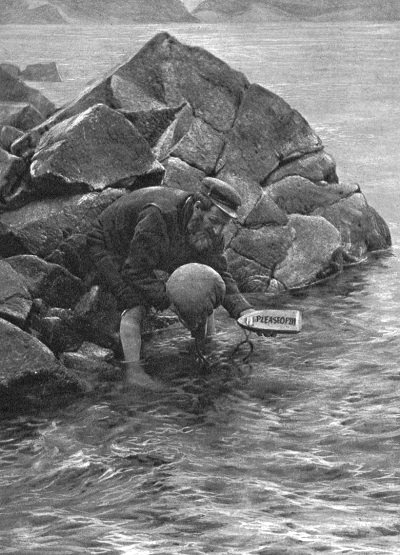

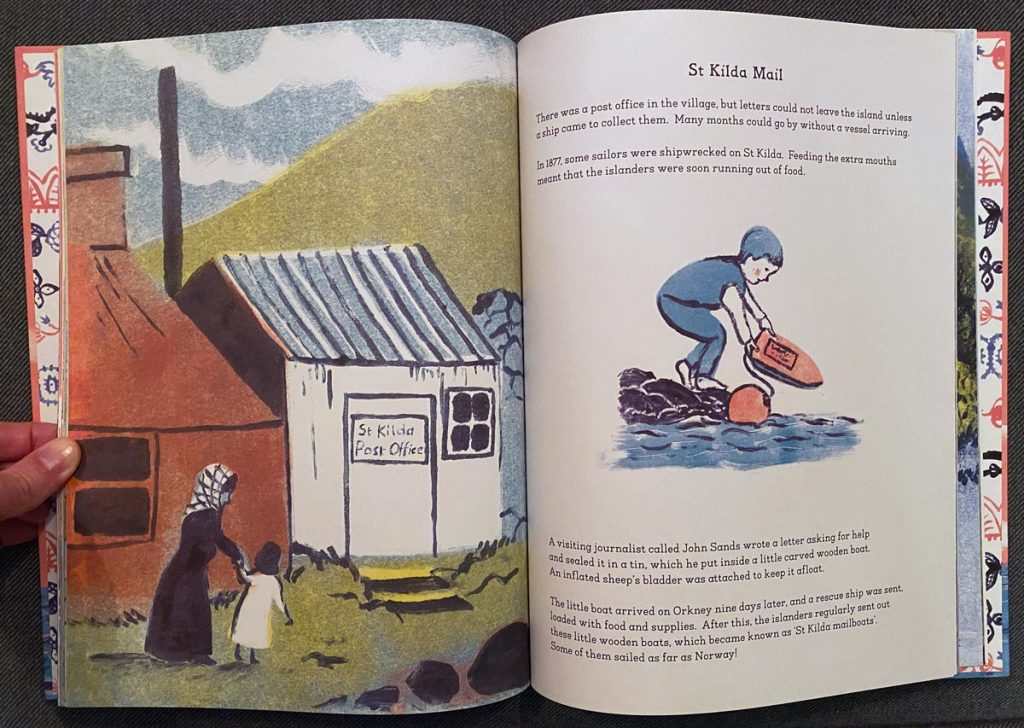

St. Kilda Mailboat

Not surprisingly, my favorite story in the book relates to postal history. The year is 1877 and an Austrian ship has wrecked on St. Kilda. The marooned sailors are unexpected mouths to feed, upsetting the delicate balance of subsistence life on the island. With food supplies taxed to a dangerous level, a Scottish journalist named John Sands (who happens to be stranded as well) took a long-shot chance and sent a distress message across the sea. He fashioned what became known as the St. Kilda mailboat and sent it off on the northwesterly winds.

“A visiting journalist called John Sands wrote a letter asking for help and sealed it in a tin, which he put inside a little carved wooden boat. An inflated sheep’s bladder was attached to keep it afloat.”

Beth Waters, from Child of St. Kilda

After nine days adrift the mailboat made landfall in Orkney, and soon after a rescue ship arrived with supplies. It worked! This initial success in reaching the outside world led St. Kildans to replicate the practice with some regularly, including numerous iterations on the design. It wasn’t foolproof, but it was their best option since the General Post Office never found a way to establish a regular route to the islands. As a final gesture to this unique communication system, one last St. Kilda mailboat was sent out before evacuation in 1930, washing ashore in Norway three months later.

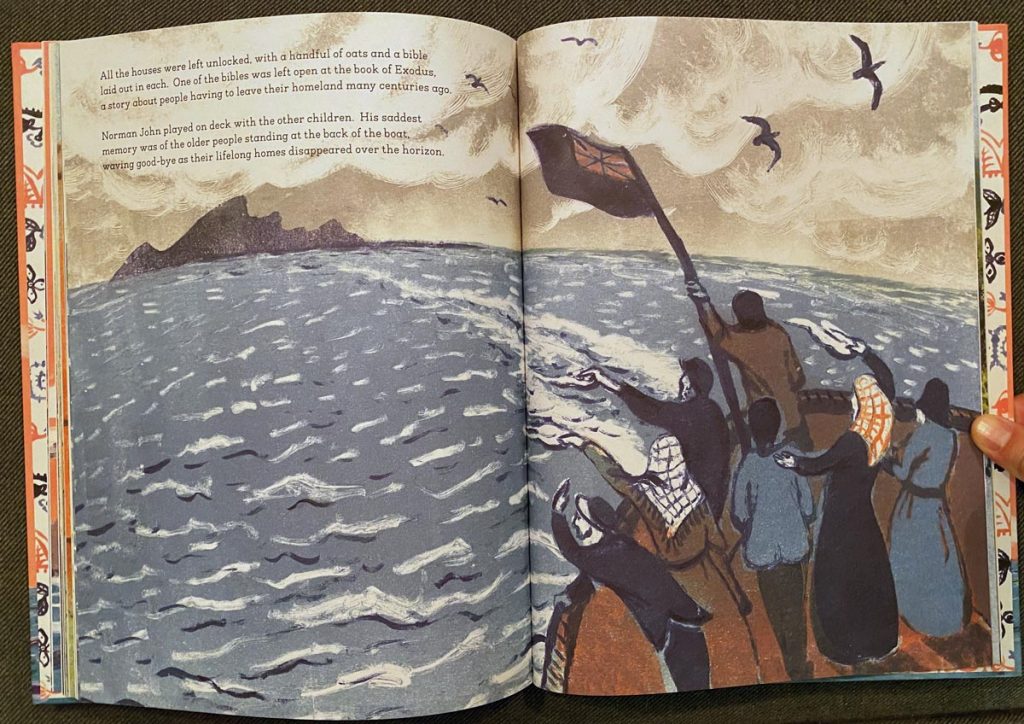

Evacuation

Near the end of Child of St. Kilda it’s revealed that 5-year-old Norman John was actually at the center of the evacuation story. His mother Mary grew ill and eventually died, which is described as a tipping point for the village to agree that it was time for evacuation. The book ends with a sad scene of the islanders waving goodbye to their abandoned home, the last in their ancestral line to inhabit the “islands on the edge of the world.” I love that this children’s book doesn’t sugarcoat the history of St. Kilda or try to paint an overly rosy picture of its history. The final words of the story are simply: “St Kilda’s unique way of life had come to an end.”

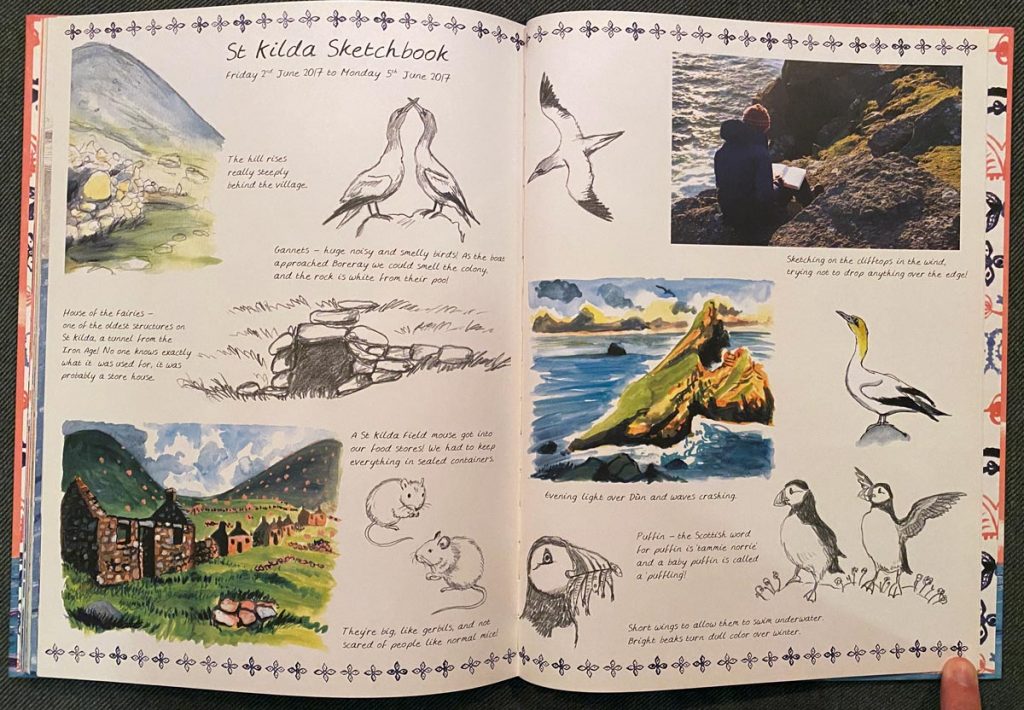

There are numerous addenda to the book, including an afterwards that talks about how the villagers were resettled, ironically getting jobs with the Forestry Commission after living on a treeless island their entire lives. There are also pages on St. Kilda today, sketches and notes from Waters’ research trip to the islands, and a remembrance of Norman John Gillies. He died in 2013, before the author could meet him, but she worked closely with his family on the details of his life. An obituary in the Economist includes a childhood photo of Gillies with his mother on St. Kilda, and notes the importance that his memories have played in our historical understanding of life on the islands.

Child of St. Kilda is Beth Water’s first book and has deservedly been recognized with awards and exhibitions. Her monoprint illustrations are beautiful, and I recommend following her on Instagram for more samples of her work. You can purchase Child of St. Kilda from your local bookseller, or via Amazon.