You could say that Tim Severin is a historical re-enactor, but that would conjure all the wrong images, of renaissance fairs and Colonial Williamsburg. At nearly 80 years old, his accomplishments are better described as experiential archaeology, recreating legendary journeys to prove they could have happened. His historical adventures are based on years of upfront study, working with scholars to decipher ancient texts and find period-appropriate technology and materials. I only recently learned about Severin’s work, through his 1978 book that documents a fascinating early project called The Brendan Voyage.

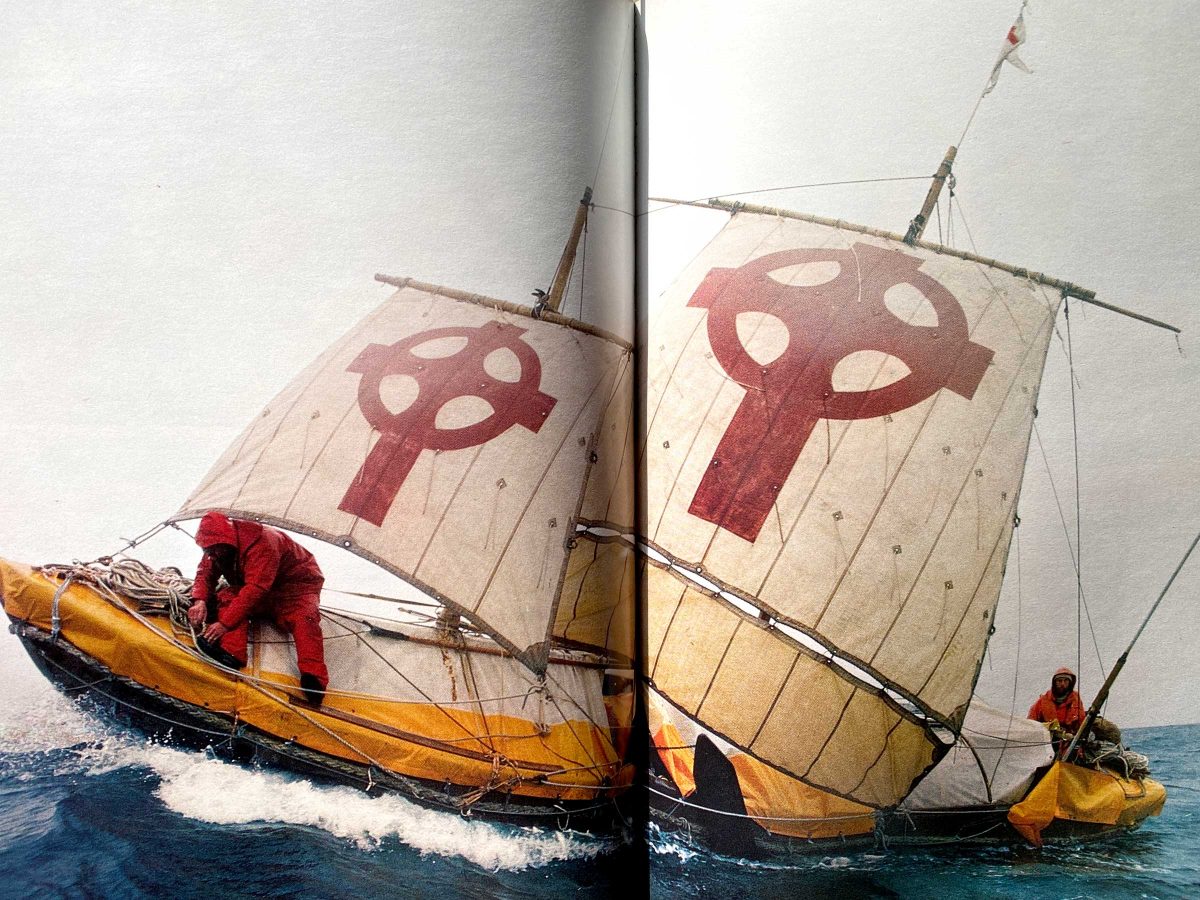

In the 6th-century, an Irish monk named St. Brendan wrote the Navigatio Sancti Brendani Abbatis (The Voyage of St. Brendan the Abbot), a document describing a westward sea journey to the “promised land” that some believe was North America. The journey included numerous stops at islands along the way, and he described seeing fantastic sights and creatures from aboard his medieval “skin boat.” Although some scholars interpret the monk’s manuscript figuratively, others subscribe to the belief that it is more travelogue than fable. That question is at the heart of The Brendan Voyage, Severin’s project to recreate St. Brendan’s journey and prove that a leather-clad sailboat could successfully traverse the North Atlantic.

“Of course, if the claim was true, then Saint Brendan would have reached America almost a thousand years before Columbus and four hundred years before the Vikings.”

The Brendan Voyage by Tim Severin, Chapter 1

The Boat

Severin’s first task, which took years of hard work, was the creation of a boat that would match the one used by St. Brendan. In The Brendan Voyage he describes a process of researching, learning, and collaborating with various experts. The energy surrounding the project is contagious, and propelled by what he calls “Brendan Luck” that seems to grace him throughout the project.

The traditional Irish curragh, which is still in use today on the west coast of Ireland, is a descendent of the boat that St. Brendan would have sailed. In modern times, canvas is stretched over the wooden frame, but the Navigatio describes a boat covered with oxhide. This was the first materials challenge for Severin, and initial tests showed that leather would deteriorate quickly in sea water.

Luckily the text provides additional clues, describing the leather as “tanned in oak bark” and coated in “grease” to make it water proof. After numerous lab studies it was proven that, indeed, oak bark was the best leather treatment. Severin found a single tannery in Britain that could help, run by the Croggon family in the Cornish town of Grampound. They had been using traditional tanning techniques since they opened in 1711, and as Brendan Luck would have it, they were enthusiastic about the project.

“So began a delightful period of work. The British leather industry took the Brendan project to heart, and what splendid people the leathermakers turned out to be.”

The Brendan Voyage by Tim Severin, Chapter 2

The manuscript describes applying “grease” to the leather, and even mentions bringing extra grease on the journey for re-application. These kinds of details further convinced Severin that he was reading the documentation of a real trip. It’s easy to determine that this must have been lanolin or “wool grease,” a wax that secreted by sheep. Severin and his crew applied it liberally to the oak bark leather and described the resulting stench as nearly unbearable.

“I wonder if you could supply me with some wool grease.”

The Brendan Voyage by Tim Severin, Chapter 2

“Yes, of course. How much do you want?”

“About three-quarters of a ton, please.”

There was stunned silence.

The remaining challenges of building Brenden, a 36-foot medieval boat were numerous and back breaking. Just the right cuts of oak and ash were found to build the mast and hull—apparently the north side of the tree is the strongest. Joints were lashed together with miles of leather stripping, and 49 overlapping ox hides were stitched together with flax cords. Brendan Luck struck again when Severin learned that John O’Connell, a master harness maker, lived nearby where the boat was being built. He joined the project and taught Severin and a team of volunteers how to stitch the thick leather. Once on the ocean their lives would depend on the quality of every stitch and knot, a reality that hung heavy over the slow and strenuous work.

For more detail on the boat’s construction I suggest checking out the article Across the Atlantic in a Leather Boat, which includes relevant excepts from the book and broader information on traditional skin boats in other parts of the world.

The Journey

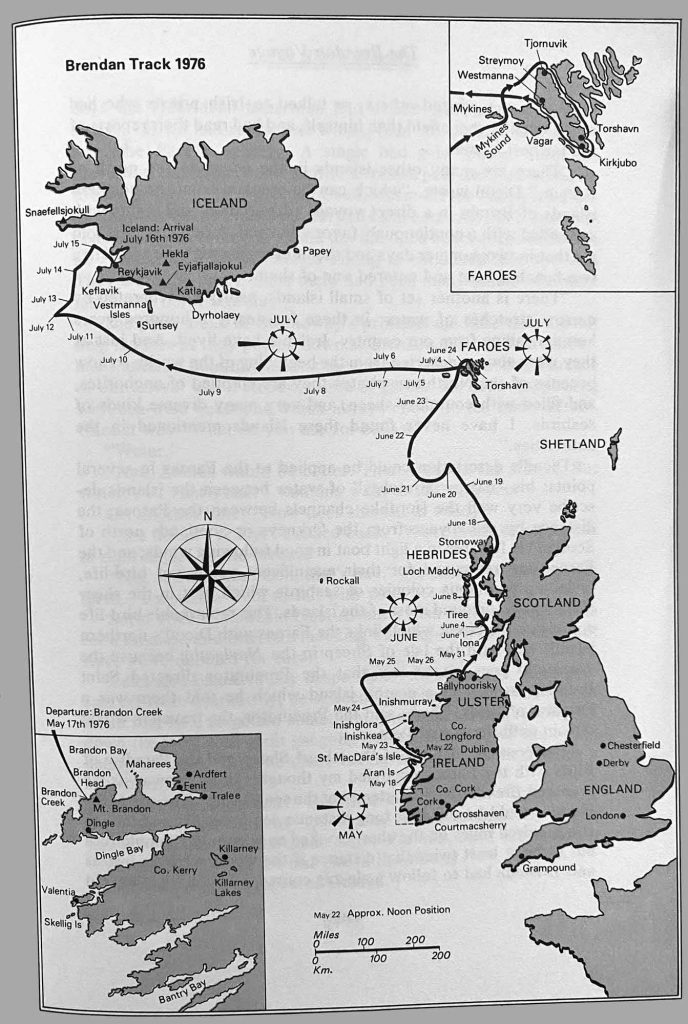

On May 17, 1976 Brenden set sail from Brandon Creek (named after an alternate spelling of the monk’s name) in County Kerry, Ireland. Every step of the voyage is detailed wonderfully in the book, including photographs from aboard the boat. Even though I knew they would make it, the vivid description of life aboard the boat was both nail biting and riveting.

The route, as with the boat’s construction, was an attempt to recreate the original journey as much as possible. Brendan followed a “stepping stone” path along the western coast of Ireland, and into the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. The first long stretch at sea was from Stornoway to the Faroe Islands, and in-between the crew was delighted by continual visits from pods of curious whales.

The Faroes are a potential match for two of the islands mentioned in the Navigatio: “The Island of Sheep” and “The Paradise of Birds.” As they approached the islands from the west, a storm in the Mykines Sound nearly forced Brendan to sail onward without landing, but they managed to maneuver north around Streymoy and land safely in the harbor at Tjørnuvík.

“More than any other people I had ever met, the Faroese understood the sea and showed their appreciation of the endeavor, and once again it was easy to detect the common bond which linked all seafarers in those hostile, northern waters.”

The Brendan Voyage by Tim Severin, Chapter 7

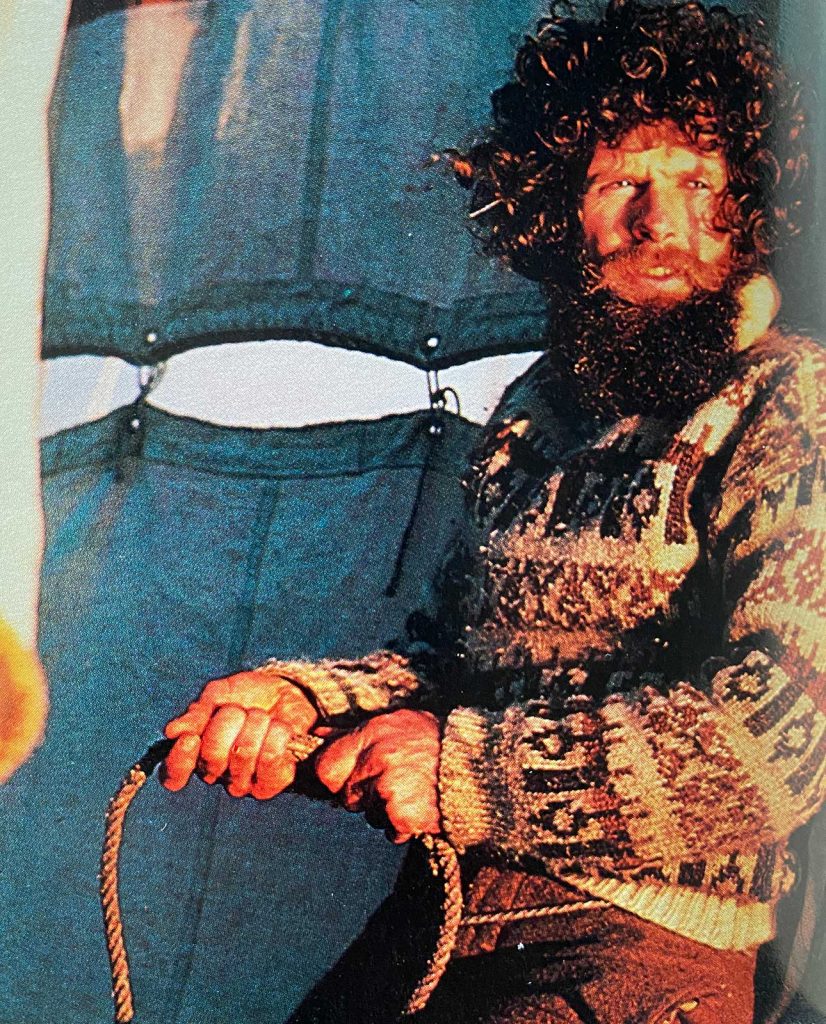

Throughout the journey, there were a few points where it became necessary for crew members to leave the project, because of injury or circumstance, and thus new people were needed to join. On the Faroe Islands, Brendan Luck would have it, that Tim Severin met Tróndur Patterson.

Today, Tróndur Patterson is a well known artist in the Faroe Islands. He’s celebrated for his paintings, sculptures, and glass art that are inspired by life at sea. Severin described meeting Tróndur as an almost fateful occurrence, beginning with an invitation to his home in Kirkjubøur where he realized that the village had a historical place name related to St. Brendan.

“What is the name of the village?” I asked.

The Brendan Voyage by Tim Severin, Chapter 7

“Kirkjubo,” she replied.

“Does it have any other name?”

“Yes, sometimes this place is called Brandarsvik.”

Tróndur was quieter than the other crew members, but he brought a Faroese confidence to life at sea. He was adept at catching seabirds using whale blubber, and had tricks for staying warm in soaking wet clothes. He also had a sixth sense for a how to respond in stormy weather, which proved invaluable during the latter half of the trip. His spare time at sea was spent drawing, and the book is filled with his illustrations.

Not only was Patursson a vital crew member on Brendan, the fateful meeting kicked off a longer collaboration with Severin. Just two years after The Brendan Voyage was complete they were reunited aboard another ancient vessel to attempt The Sindbad Voyage.

From the Faroe Islands the crew sailed to Iceland, which St. Brendan called the “Island of Smiths” in an apparent description of a volcanic eruption. After bringing the boat ashore in Reykjavík, it was clear that Brendan had fared well. The leather hull was coated in barnacles, but without a single tear or hole. Still, after weeks of waiting for favorable weather, it was determined that the sea between Iceland and Greenland was simply too rough to continue; sailing season was over. They decided to wait until the following spring and docked Brendan in Iceland for the winter.

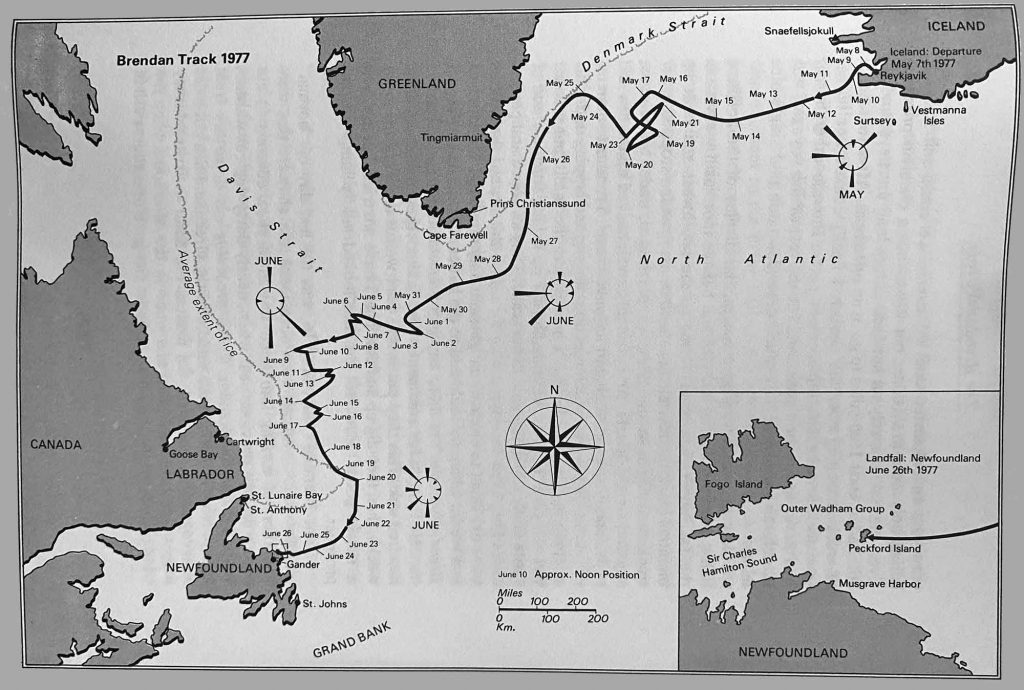

It had always been a good guess that the last leg of the trip would be the hardest, since the waters around Greenland and Labrador are sparsely inhabited and treacherous. That turned out to be true for Brendan, which nearly capsized in stormy weather and suffered damage to her leather hull while navigating through icebergs. It was touch and go at times, but of course, in the end, they were successful. On June 26, 1977 the voyage was completed by landing on Peckford Island, Newfoundland. In the documentary, which includes film from land-based crews as well as onboard footage, we see excited crowds awaiting the boat’s arrival and an impromptu parade celebrating the sailors’ accomplishment.

A successful voyage of course doesn’t prove that Irish monks came to North America a thousand years before Columbus, but it does show that they could have using the technology available to them. I find The Brendan Voyage fascinating for both its historical significance and the way it transpires across so many of my favorite islands. I’m also impressed by how well documented it was, the detail of the book and accompanying film. I’m surprised I hadn’t heard about this adventure before, given that it concluded a full year before I was born. I guess I should consider it Brendan Luck that it finally crossed my path.

I’d suggest getting a physical copy of the The Brendan Voyage book, perhaps seeking out the original 1978 hardcover to ensure it has all of the photographs, maps, and illustrations by Tróndur Patursson.

Whether you read it or not, I highly recommend watching the documentary, which is available on YouTube in two parts and is just under an hour in total.

Finally, you might be interested in this Story Map about The Brendan Voyage, which includes accurate Google Maps showing the route across the North Atlantic.