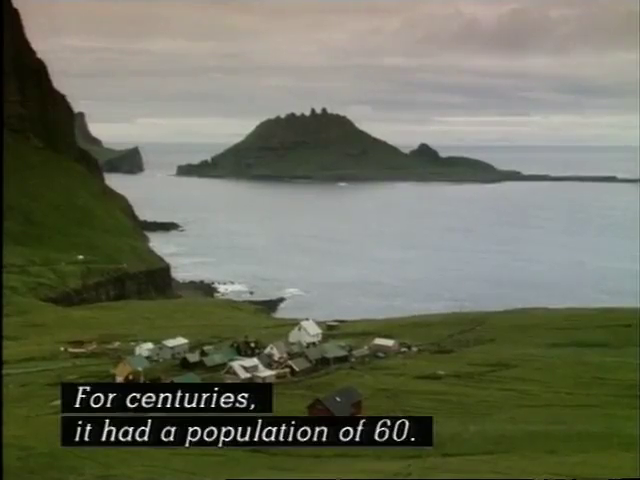

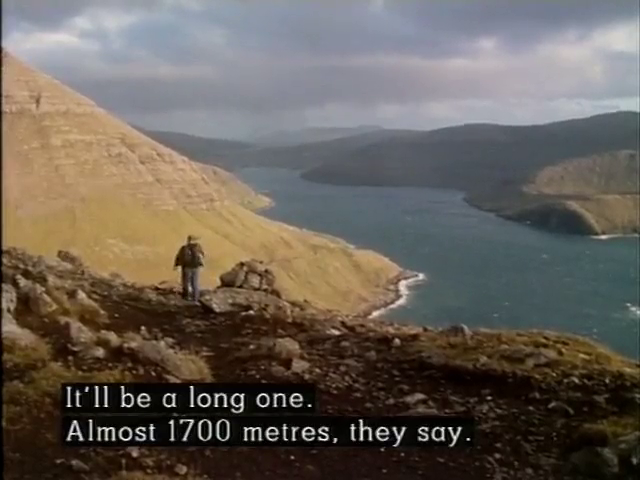

The film 1700 Meters from the Future, by Ulla Rasmussen, is a feature length documentary from 1990 set in the village of Gásadalur in the Faroe Islands. Tucked into a remote valley in the northwest corner of Vágar island, Gásadalur is surrounded by steep fells on three sides and a treacherous ocean cliff on the fourth. For centuries, the population of the village held steady at 60 people, but by the time of the film it had declined to only 16 adults and a 9-year-old boy. The title refers to the plan to build a tunnel through the Knúkarnir mountain, connecting Gásadalur to the village of Bøur. Interviews with townspeople, all of them multi-generational residents, convey their hopes for this connection to the outside world, while highlighting concerns about change, long-standing economic struggles, and challenges caused by Faroese land use policies.

Tunnels in the Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands is a compact archipelago, most of its eighteen islands tightly clustered together and none of them particularly large. But proximity can be deceiving, and historically the extreme terrain and unpredictable North Atlantic waters have made travel between the islands quite challenging. Faroese literature makes extensive use of this difficulty as a plot device, with characters often stranded on inaccessible islands. It also led to unique social structures, such as the skjúts postal system, a relay process where each village had the duty (and risk) of transporting parcels to the next village.

In the 1960s a transformation began, as the Faroese began building tunnels to replace the mountain footpaths and dangerous boat routes. Blasted through basalt hills and bored beneath the sea, these tunnels connected disparate villages and made for easy transport to and from the capital of Tórshavn. Unlike Newfoundland, another place where villages historical developed around sea travel, the Faroe Islands has prioritized access over resettlement. In the film, a highway department employee puts it succinctly, saying “I think the tunnels have enhanced the sense of community here. And that is so valuable it can’t be calculated in money terms. It can never ‘pay’ to forge a road out to a tiny community.”

There are now 22 tunnels in the Faroe Islands, with more on the way. Some are simple and primitive, a one-lane unlit hole through a mountain with periodic divots to pull over when another car is heading the opposite direction. Others are modern engineering marvels, like the recently completed Eysturoy Tunnel, the second longest sub-sea tunnel in the world complete with underwater roundabout featuring artwork by Faroese artist Tróndur Patursson.

Getting to Gásadalur

Today, the Gásadalur valley is one of the most popular tourist destinations in the Faroe Islands, a convenient 15 minute drive from Vágar airport. Most people go to see the Múlafossur waterfall, a stunning and dramatic scene of water tumbling over an ocean cliff with the village as a backdrop. It’s one of the most photographed scenes in the country. But before the tunnel, as we see in the film, it would have taken a determined journey to visit this site.

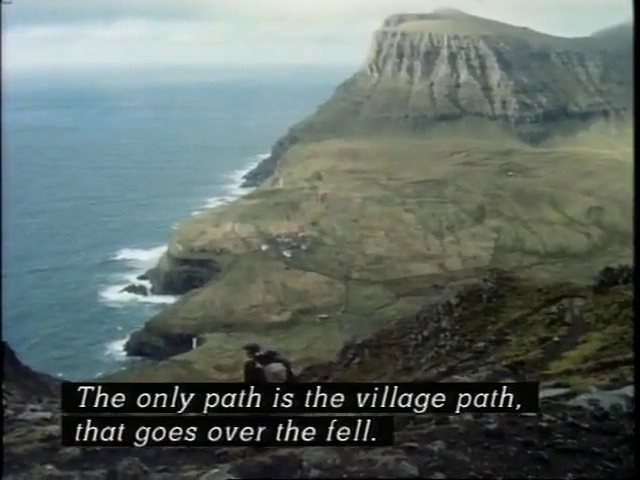

For centuries, the primary way to Gásadalur was to walk over the mountain. Referred to today as the old postal route, this 5km trail takes roughly three hours and offers dramatic views of Tindhólmur and Mykines along the way. This route was used to transport small to medium-sized items by foot, including coffins when one of the villagers past away. In describing these funeral processions over the fell a villager notes that they would pause to rest only once, upon reaching a designated spot past the summit known as “coffin rock.”

Larger goods could be brought by boat, although the steep cliffs made transport up to the village difficult. A man in the film recalled that the steps down to the landing were constructed in 1939. “We had to carry everything up from the landing” he said, pointing to the stove behind him as a particularly difficult example.

In 1983 the helicopter service began. Helicopters are used throughout the Faroe Islands, providing an essential link to remote islands like Fugloy or Stóra Dímun. In the film we meet a 32-year-old Gásadalur native who moved away, but came back to run the helipad. Introduction of the helicopter meant that large items like appliances and building supplies could airlifted, although even that had limits. To bring in a construction digger they had to disassemble it into numerous components that were under the weight limit.

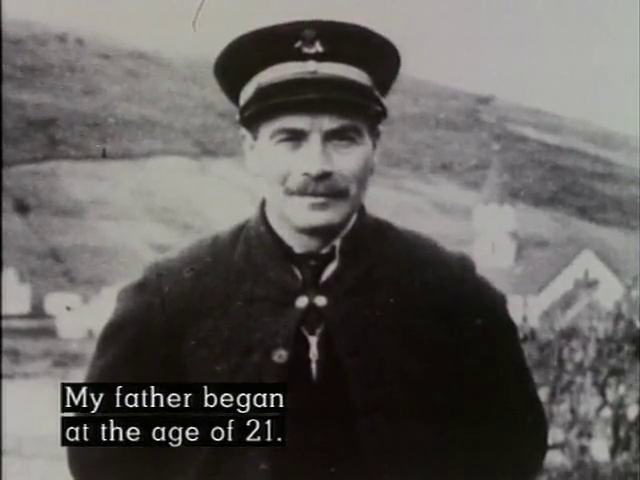

The postman we meet is a second generation mail carrier whose father was the first in Gásadalur. He recalls how his father walked the postal route for 56 years, leaving early in the morning each day and “in the winter, it was dark when he got home.” Despite the helicopter, he still walks the route three times a week, since foggy weather commonly makes flying unsafe.

Life Before the Tunnel

The film features many of the 16 residents, most of whom were born there. The only child is 9-year-old Pól Sigmund, who lives with his grandparents. He goes to school every second week, when a teacher travels from Mykines. In a sign of more populous times, the private tutoring actually happens in a dedicated school house. On alternate weeks he helps adults take care of the animals, and only gets to play with other children when they visit during the summer months.

The economic life in Gásadalur revolves around animals, primarily cattle but also sheep and birds. Outside of the delivery mail, or managing the helipad, there are no paid jobs in Gásadalur — but as one resident notes, “Gásadalur has always been a good larder.” Older residents share stories of bountiful fowling, catching 100s of puffins a day, but also of tragedy on the bird cliffs.

Cattle and sheep graze in the grassy outfields, and the film shows seasonal herding of both. Although I expected to learn that Faroese sheep were prevalent, I was surprised to learn that at this time the price of wool had crashed:

“Wool has become a major problem for us. Wool prices have fallen so much that selling it can’t pay. We have burned wool, or buried it. It’s not much fun gathering wool when you can’t get rid of it.”

Gásadalur resident

Land Rights

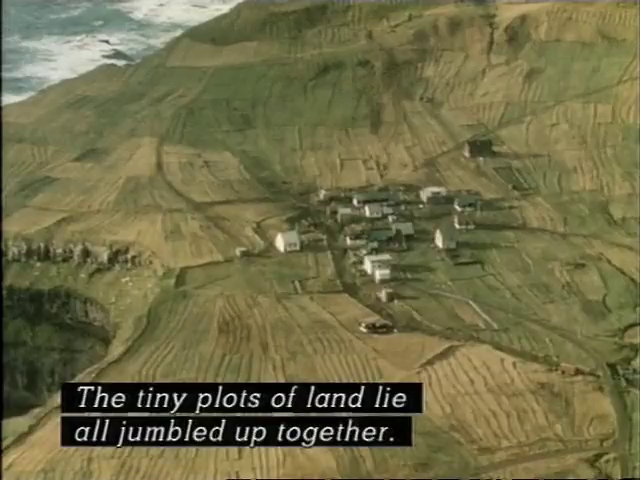

One of the scenes in the film involves discussions of a proposed change to land distribution. Land rights have a complicated history in the Faroe Islands, where owning land in a village can be tied to grazing and hunting rights in the outfields. I first learned about this complexity in the book The Faroe Islands by Liv Kjorsvik Schei and Gunnie Moberg, which provides a detailed overview. The authors note that every time a landowner died, “the land would be divided among his heirs, every field being divided into narrow strips so that the heirs could share and share alike.” This has led to a situation where even small villages such as Gásadalur have 100s of private lots, “too small to run on any kind of commercial basis.” Single owners may own scores of tiny non-contiguous plots, making it difficult for any individual to put the land to productive use.

“More than 100 people own land here. The law of inheritance is responsible for that.”

Gásadalur resident

The film captures a planning meeting in which discussions are held to reapportion the land, in an attempt to create larger contiguous holdings. “The plots of land lie all jumbled up together” says one man, while others complained 2/3 of the land is owned by people who don’t even live there. There’s a market for these plots, and they’re sometimes sold without buyers or sellers even visiting the village. “People with nothing to do with the village are buying up land. People from Torshavnn for example.” The residents of Gásadalur can’t afford to pay.

Not everyone seemed happy with the process. There were questions about how this would effect hunting rights, and others worried that it should have been more strategically timed with the upcoming tunnel opening:

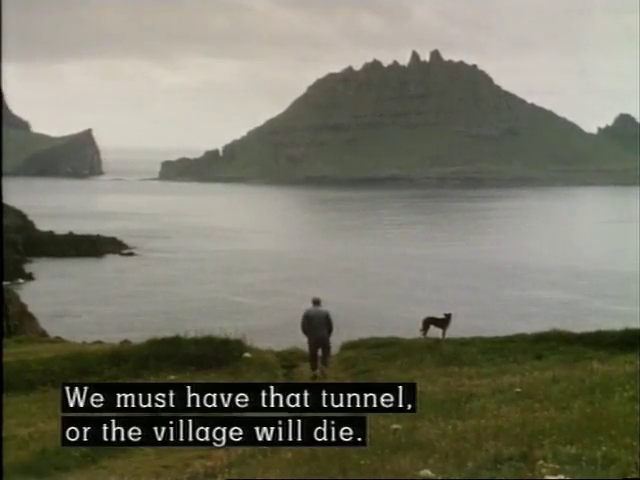

“The redistribution of land has come too soon. We should have finished the tunnel first, so people would move here and be able to buy land. We need new people. There are hardly any able-bodied people left. We must have that tunnel, or the village will die. That’s for sure.”

Gásadalur resident

Looking to the Future

The film ends with reflections from residents on what they hope the tunnel will bring. There’s excitement that new people might move to Gásadalur, mixed with concerns that people might also move out:

“Some people move when roads are built to their villages, but a few years later they move back again.”

Gásadalur resident

Others were concerned that easy access means outsiders who own the land will decide to farm it themselves, revoking the leases and livelihoods of current residents:

“When the tunnel comes the landowners will come. They’ll come to farm it themselves. So anyone who’s leased land has had it. They won’t be able to keep cattle or sheep.”

Gásadalur resident

The couple who take care of the village’s only boy are excited about the possibility of more families making Gásadalur their home:

“People will come and live in the valley. They can work elsewhere. Then there will be little children again.”

Gásadalur resident

And one man is convinced that the tunnel will lead to holiday cottages hosting raucous parties:

“The tunnel isn’t just a blessing. It’ll be good and bad. Specially if they’re allowed to build holiday cottages. Then they’ll have parties. They’ll throw bottles around so you can’t go out without shoes. But I suppose the tunnel will have to come, or the village will die. No doubt about that. The helicopter can’t keep it alive, it can only prolong the agony.”

Gásadalur resident

Epilogue

The final scene of the film shows villagers listening to a radio broadcast as a news story details government budget cuts. It specifically mentions the highway department, and the need to pause planned road works projects. At the beginning of the film, it’s mentioned that the tunnel had been talked about for a decade. Ultimately it took another 13 years after the release of 1700 Meters to the Future to connect Gásadalur by road. The Gásadalstunnilin was opened to pedestrians in 2003, and finally for vehicles in 2006.

The Faroe Islands continues to build tunnels, the largest in-process project being the undersea link between the islands of Streymoy and Sandoy. As I was writing this post a news story caught my eye, the headline proclaiming that the Sandoy Tunnel was “just 1,750 meters from breakthrough.” The future will be here soon.

You can watch the entire documentary below:

I have not attributed the quotes above to specific individuals because people in the film are not referenced by name. The credits, however, list the following contributors: Solberg Henriksen, Pauli Jacobsen, Hjalgrim H. Petersen, John, Rakul and Petra Josensen, Pól and Hedith Mikkelsen, Pól Sigmund, Hanna Mikkelsen, Dávur and Joan Dávur Joensen, Petur Joensen, Heini Zachariassen.